Copying Accelerated Video Decode Frame Buffers

출처:https://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/copying-accelerated-video-decode-frame-buffers

Abstract

Using conventional copying methods can yield very poor performance when the source data is in “uncacheable” memory, as when video decode is being done with hardware acceleration, but an application needs to quickly obtain copies of decoded frame buffers for additional processing.

This paper explains best known methods for improving performance of data copies from Uncacheable Speculative Write Combining (USWC) memory to ordinary write back (WB) system memory. Sample code is included for a fast copy function based on those methods, as well as sample code illustrating how that copy might be called in an application using the Microsoft DXVA2 (DirectX Video Acceleration 2) libraries for hardware accelerated video decode to copy video frames from USWC to WB memory buffers.

Copying data to USWC memory or within WB memory is not covered, nor is integration with other video acceleration APIs.

[Editor: Click here to download this paper in PDF format (364MB)]

Objective

Copying data from USWC memory can exhibit very poor performance with conventional copy methods, such as applying the memcpy() function, or writing a simple copy function using the MOVDQA SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) instruction to load and store data. This white paper should be useful for improving copy performance of software that must read video frames decoded by a hardware decode accelerator from USWC graphics memory into a system memory buffer for further processing.

Streaming load and store instructions (sometimes referred to as “non-temporal” memory operations), such as MOVNTDQA and MOVNTDQ, provide hints that allow the CPU to access memory more intelligently, and in particular for reading data from USWC memory. (Note that MOVNTDQA is part of the SSE4.1 instruction extensions supported on recent Intel processors.) Load bandwidth from sequential memory addresses using streaming loads can be an order of magnitude faster than with ordinary load instructions.

However, simply replacing MOVDQA with MOVNTDQA and MOVNTDQ in a simple copy loop is generally not sufficient to achieve the best possible performance. This paper will explain why this can be true, and demonstrate a software method to consistently achieve excellent memory copy bandwidth.

The demonstrated methods may be used to copy video frames decoded by a hardware video accelerator, to allow software processing of the video frames. This paper will show an example of integration with a DirectX* Video Acceleration 2 (DXVA2) based application.

Fast USWC to WB Memory Copy

Overview of the Fast USWC Copy

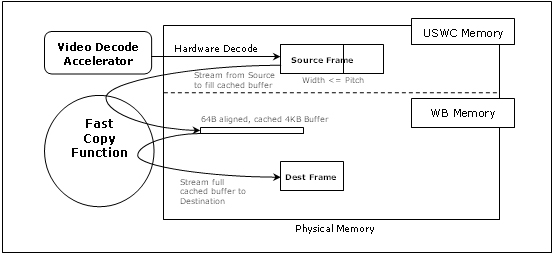

Figure 3-1 is a quick summary of the current best known algorithm to copy data buffers from USWC memory to WB system memory. Figure 3-2 illustrates the same process graphically.

Figure 3-1. Summary of the Fast USWC to WB Copy

Fill a 4K byte cached (WB) memory buffer from the USWC video frame Load a cache line’s worth (64 bytes) of data from a 64 byte aligned address into four SIMD registers using MOVNTDQA. Use MOVDQA to store the registers’ data to a 4Kbyte system (write back) memory buffer that will be re-used over and over - so that the buffer stays in first level CPU cache, rarely being flushed to memory. This buffer should also be 64 byte (cache line) aligned. Repeat above two bullets in step 1 until the 4KB buffer is full. Copy the 4K byte cache contents to the destination WB frame Once the buffer is full, read from it using MOVDQA loads - again loading one full cache line at a time - to SIMD registers. Write those registers to 64 byte aligned destinations in the system memory buffer using MOVNTDQ - again giving the processor a hint to minimize bus bandwidth and cache pollution. Repeat above two bullets in step 2 until all data is copied from the 4KB buffer. Repeat steps 1 and 2 until the whole frame buffer has been copied.

Figure 3-2. Graphical View of the Fast Copy Process

The most noteworthy aspect of this algorithm is the use of two separate loops for loading data from USWC memory and storing it to a system memory buffer, with an intermediate 4KB buffer in cached memory. This is done to optimize the use of the streaming loads and stores.

Streaming Load and Store Background Ordinary load instructions pull data from USWC memory in units of the same size the instruction requests. By contrast, a streaming load instruction such as MOVNTDQA will commonly pull a full cache line of data to a special “fill buffer” in the CPU. Subsequent streaming loads would read from that fill buffer, incurring much less delay.

A fill buffer is allocated for each streaming cache line load, but there are only a handful of fill buffers on a typical processor. (Consult the Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual for the number of fill buffers in a particular processor; typically the number is 8 to 10. Note that sometimes these are also referred to as “Write Combining Buffers”, since on some older processors only streaming stores were supported.) To avoid reloading the same cache line, it is best to quickly and consecutively read all the data of each cache line. That also frees the fill buffer for other use as soon as possible.

Storing data to WB system memory with MOVNTDQ avoids the usual “read before write” (in which a cache line that will be written is first loaded into the CPU cache hierarchy). Streaming stores to the same WB cache line may be accumulated in a fill buffer, to be written to memory or the cache hierarchy in a single cache line transaction.

Again, with a limited number of fill buffers, it is important to finish using them as quickly as possible. Consecutively issuing all streaming stores needed to fill a cache line minimizes the chance that a fill buffer gets reused prematurely, which would result in the stores being written to memory or cache much less efficiently. (See the Intel® Architecture Optimization Reference Manual for more details.)

Why a Small Cached Buffer is Used If the streaming loads and stores of the copy algorithm were in the same loop, they would compete for fill buffers, resulting in more cache lines being reloaded or written with partial data. (The out of order execution of most recent Intel processors can contribute to this issue. Loads that are after some stores (in instruction execution order) may begin executing before those stores have completed, so long as they don’t depend on those stores. So a streaming load might “go early” and interfere with a streaming store, if they are not kept separated.)

However, when data is stored and loaded from memory locations that are currently represented in the first level CPU cache, no fill buffer is needed - the data combines directly in the cache, or is taken directly from the cache. So long as the buffer continues to be used frequently, accesses to it will rarely generate any additional memory bus traffic. This is why a buffer of cacheable system memory is used as an intermediate destination for the first loop, and as the source for the second loop. Ordinary (MOVDQA) loads to and stores from the cached 4KB buffer won’t interfere with the streaming operations.

The 4KB size was chosen to be small enough to fit in the first level cache, large enough to keep many streaming loads well separated from many streaming stores, yet not so large that other data could not use the cache. 4KB also is large enough to hold two lines of a 1920 pixel wide video frame. A buffer size of 2KB or 8KB would work about as well.

A Sample Implementation Figure 3-3 shows this algorithm coded with C++. Note that the _mm_store_si128 and _mm_load_si128 intrinsics will compile to the MOVDQA instruction, while the _mm_stream_load_si128 and _mm_stream_si128 intrinsics compile to the MOVNTDQA and MOVNTDQ instructions, respectively. The sample implementation makes several simplifying assumptions, such as using the same pitch (which is assumed to be a multiple of 64 bytes), and expecting 64 byte alignment of every row of the source, cached 4K buffer and destination buffers. To the extent possible, these would be good features to include in new implementations, as they contribute to obtaining the best possible performance. The MOVNTDQA streaming load instruction and the MOVNTDQ streaming store instruction require at least 16 byte alignment in their memory addresses.

The sample implementation also illustrates a few more performance enhancements, that will be described below.

Figure 3-3. Frame Copy Function

// CopyFrame( )

//

// COPIES VIDEO FRAMES FROM USWC MEMORY TO WB SYSTEM MEMORY VIA CACHED BUFFER

// ASSUMES PITCH IS A MULTIPLE OF 64B CACHE LINE SIZE, WIDTH MAY NOT BE

typedef unsigned int UINT;

#define CACHED_BUFFER_SIZE 4096

void CopyFrame( void * pSrc, void * pDest, void * pCacheBlock,

UINT width, UINT height, UINT pitch )

{

__m128i x0, x1, x2, x3;

__m128i *pLoad;

__m128i *pStore;

__m128i *pCache;

UINT x, y, yLoad, yStore;

UINT rowsPerBlock;

UINT width64;

UINT extraPitch;

rowsPerBlock = CACHED_BUFFER_SIZE / pitch;

width64 = (width + 63) & ~0x03f;

extraPitch = (pitch - width64) / 16;

pLoad = (__m128i *)pSrc;

pStore = (__m128i *)pDest;

// COPY THROUGH 4KB CACHED BUFFER

for( y = 0; y < height; y += rowsPerBlock )

{

// ROWS LEFT TO COPY AT END

if( y + rowsPerBlock > height )

rowsPerBlock = height - y;

pCache = (__m128i *)pCacheBlock;

_mm_mfence();

// LOAD ROWS OF PITCH WIDTH INTO CACHED BLOCK

for( yLoad = 0; yLoad < rowsPerBlock; yLoad++ )

{

// COPY A ROW, CACHE LINE AT A TIME

for( x = 0; x < pitch; x +=64 )

{

x0 = _mm_stream_load_si128( pLoad +0 );

x1 = _mm_stream_load_si128( pLoad +1 );

x2 = _mm_stream_load_si128( pLoad +2 );

x3 = _mm_stream_load_si128( pLoad +3 );

_mm_store_si128( pCache +0, x0 );

_mm_store_si128( pCache +1, x1 );

_mm_store_si128( pCache +2, x2 );

_mm_store_si128( pCache +3, x3 );

pCache += 4;

pLoad += 4;

}

}

_mm_mfence();

pCache = (__m128i *)pCacheBlock;

// STORE ROWS OF FRAME WIDTH FROM CACHED BLOCK

for( yStore = 0; yStore < rowsPerBlock; yStore++ )

{

// copy a row, cache line at a time

for( x = 0; x < width64; x +=64 )

{

x0 = _mm_load_si128( pCache );

x1 = _mm_load_si128( pCache +1 );

x2 = _mm_load_si128( pCache +2 );

x3 = _mm_load_si128( pCache +3 );

_mm_stream_si128( pStore, x0 );

_mm_stream_si128( pStore +1, x1 );

_mm_stream_si128( pStore +2, x2 );

_mm_stream_si128( pStore +3, x3 );

pCache += 4;

pStore += 4;

}

pCache += extraPitch;

pStore += extraPitch;

}

}

}

Notes on the Sample Implementation The sample implementation in Figure 3-3 illustrates several more subtle enhancements of the fast copy function:

An _mm_mfence() intrinsic is used between the loading and storing sub-loops. The load sub-loop reads the full pitch of the source buffer, while the store sub-loop stores only the actual width of the video frame - even though both buffers have the same pitch. (See Table 3-1 below for the performance impact of these and other aspects of the fast copy algorithm.)

Also, in order to have a compact but correct copy function, a conditional test loop was included inside the outer loop, to handle the possibility that fewer rows get copied in its last iteration. It would be better to eliminate that test or find a way to move it out of the outer loop.

Why MFENCE Is Used One key refinement of the fast copy algorithm is demonstrated in the sample code - the use of the _mm_mfence() intrinsic, from which the compiler generates the MFENCE instruction. MFENCE tells the processor to make sure all previous memory operations - loads and stores - are finished before allowing any subsequent memory operations to begin.

The effect of MFENCE is to completely separate the streaming loads of the first sub-loop from the streaming stores of the second sub-loop. This is beneficial, since most modern Intel processors use “out of order” processing - meaning that it is entirely possible for some stores of the second loop to happen before the last of the loads of the first loop have finished. A bit less obviously, since the outer-most loop brings execution back to the first sub-loop, loads of the next iteration of the first sub-loop could have started before the last stores of the previous iteration second sub-loop have finished. MFENCE eliminates those sorts of overlapping memory operations.

Why the Inner Loop Iteration Counts Differ The frame buffer on the hardware device may be stored with a pitch (byte length from row to row of pixels) that is greater than the width of the frame being copied. Through experimentation (on a system using Intel integrated graphics), it was found that the best performance was obtained by copying the entire buffer pitch width from the USWC frame buffer into the 4KB buffer, then storing only the frame width to the system memory buffer.

For example, with a 1280 pixel wide frame being copied, the USWC frame buffer used a pitch of 2048 (2KB). The data was copied to the 4KB buffer with a full 2KB pitch as well, and then only the 1280 bytes of interest were saved to the system buffer. However, performance loading only the frame’s width of pixels per row to the cache came in a close second, and this performance aspect could be system or workload dependent. (See the last two rows of Table 3-1, below.)

Comparing Alternative Frame Copy Implementations

Table 3-1 shows an example of performance of alternative frame buffer copy algorithm implementations, including a baseline using the commonly used memcpy standard C library function. Tests were run on a pre-release 2.67ghz dual core 32nm Intel® Core™ i5 processor-based platform with 2GB of 1333mhz DDR3 system memory and Intel integrated graphics supporting h.264 video decode acceleration. Performance will vary depending on the system tested, and may be different on the released version of the tested configuration.

Table 3-1. Performance of Alternative USWC Memory Frame Copy Methods

Copy Method, for 1280 wide frame, pitch 2048 Performance in Mbyte/second MEMCPY, copying full frame buffer in one call 90 Streaming load & store 64 byte cache lines in one loop, copying full frame buffer 745 Streaming load & store, via 4K buffer, load pitch, store frame width 945 Streaming load, MOVDQA store, via 4K buffer, load pitch, store frame width 985 Streaming load, MOVDQA store, via 4K buffer, load pitch, store frame width, use mfence 1025 Streaming load & store, via 4K buffer, load pitch, store frame width, use mfence 1175 Streaming load & store, via 4K buffer, load & store frame width, use mfence 1125

NOTE: Video frame copy bandwidth from USWC to WB memory, relative to memcpy() performance; higher is better.

Streaming loads used the MOVNTDQA instruction, streaming stores used the MOVNTDQ instruction. The term “load pitch” in the table means that the copy method copied the all bytes of the frame buffer to the cached 4KB buffer. Loading or storing “frame width” means that only actual pixels of the video frame were copied, ignoring left over bytes in the frame buffer due to a pitch larger than the frame width.

Performance was measured in terms of useful video pixel data copied, not raw bytes per unit time, since some algorithms accessed data (e.g. loading full pitch) that were not part of the video. Since the tested resolution was 1280 pixels wide on a pitch of 2048 bytes, performance of the “load pitch” and “copying full frame buffer” methods will improve substantially for wider frame widths such as 1920 horizontal pixels. As the best method does “load pitch”, it should remain the best for wider frame widths.

Other Possible Improvements

Simplification

As Table 3-1 shows, the performance benefit of storing only the frame width (in the second set of nested loops of Figure 3-3) instead of copying the full frame buffer is minor, and of course will be even smaller if width and pitch are very similar. So long as the source and destination buffers have the same pitch and 64 byte alignment, a USWC to WB copy function could simply copy contiguous 4KB blocks of 64 byte aligned data. Instead of two sets of nested inner loops, there would be two individual inner loops that ignore “rows” “width” and “pitch” to simply read and write 4KB of data to and from the cached buffer (respectively) - of course making sure not to read or write past the end of the buffers.

If the video frame buffer pitch equals the width for both source and destination frame buffers, this simpler copy function should have performance as good or slightly better than the sample code of Figure 3-3.

Multi-Threading If an application targets a multi-core processor, each physical core has its own set of fill buffers. It may be possible to gain additional performance benefits by having two or more threads, each running a copy from independent areas of USWC memory, each “affinitized” to a different physical core. (Logical processors on the same physical core using Intel’s symmetric multi-threading technology share fill buffers, so using two threads on the same physical core should not be beneficial.)

However, thread synchronization overhead can be large enough to become a limiting factor on frame buffer copies. Or a single core may hit limits imposed by the video or graphics device from which frames are being copied. Tests on the same system used for the table above did not demonstrate any performance benefits from two threads.

Processing “In Flight” If an application will be processing an entire copied frame of video in a sequential fashion, it may be possible to process the data before writing it to the system memory buffer, in a specialized “copy and modify” function. The processing could be done either during the load to the cache, or during the store to the system buffer - but care must be taken to avoid memory loads or stores that might evict data from the fill buffers, or result in the cached buffer being evicted from first level cache.

DXVA Decode Integration

Video Frame Buffer Copying Order

A DXVA enabled decode application will need to keep track of Direct3D* surfaces representing graphics memory buffers for frames being decoded in hardware. Once a frame has been decoded into a buffer, a pointer to the USWC memory buffer can be obtained, and the fast copy method described above can be used to create a copy in system memory using code similar to that in Figure 4-1.

It would be possible to copy each frame as soon as it is decoded, but most video codecs require that frames be decoded in an order other than their display sequence, which would be reflected in the order the copied frames become ready for further processing. Typically, copying should be done when the next frame in display sequence (i.e. the order in which the frames were captured and play back) has been decoded.

If video is being displayed for viewing during the copy operation, the frame copy might be done where the decode application is scheduling a decoded frame to be the next displayed. Care should be taken that the copy does not delay displaying the frame. However, even for high definition (e.g. 1920x1080) frame sizes, copying with the method described here will typically require only a few milliseconds on any recent processor in the Intel® processor family.

In the Media Player Classic - Home Cinema open source code, the CopyBackTest() function in Figure 4-1 was called within the DXVA2 handling case of the function CDXVADecoder::DisplayNextFrame() in file DXVADecoder.cpp of the MPCVideoDec library. To provide a reference to the video frame to copy, m_pPictureStore[nPicIndex].pSample was passed for the IMediaSample pointer parameter. The destination buffer and caching buffer being passed in are assumed to be 64 byte aligned, as required by the CopyFrame() function in Figure 3-3. (While calling the copy before delivering the frame to the output pin of the decode filter did not seem to cause any problems, it is probably best to call it after that.)

An application that merely scales the video frame size and re-encodes video with the same codec, might prefer to copy and process frames in the out of sequence order if the same ordering can be used for the new encoded stream. That experiment was not attempted as part of the work summarized by this paper.

Figure 4-1. Calling the Frame Copy Function from DXVA2 code

// CopyBackTest

// EXAMPLE USE OF CopyFrame() FUNCTION

// PASSES IN POINER TO iMediaSample, BUFFER TO FILL, CACHING BUFFER

//

// (NOTE: Error checking left out for brevity.)

typedef unsigned int UINT;

#define NV12_FORMAT 0x3231564e // 2 1 V N

void CopyBackTest( CComPtr<IMediaSample> pSampleToDeliver, void *pSysFrame,

void * pCacheBuf )

{

D3DSURFACE_DESC surfaceDesc;

D3DLOCKED_RECT LockedRect;

UINT width, height, pitch, format;

void * pSourceFrame;

CComQIPtr<IMFGetService> pSampleService;

CComPtr<IDirect3DSurface9> pDecoderRenderTarget;

pSampleService = pSampleToDeliver;

pSampleService->GetService( MR_BUFFER_SERVICE,

__uuidof(IDirect3DSurface9),

(void **) & pDecoderRenderTarget );

// INFORMATION MIGHT BE GATHERED ONCE, IF WON'T CHANGE

pDecoderRenderTarget->GetDesc( & surfaceDesc );

width = surfaceDesc.Width;

height = surfaceDesc.Height;

format = surfaceDesc.Format;

if ( format == NV12_FORMAT )

{

height = 3 * height / 2; // FULL Y, SUBSAMPLED UV PLANES

}

else

{

// OTHER FOURCC SUPPORT

}

// THIS INFORMATION MUST BE GATHERED FOR EACH FRAME

pDecoderRenderTarget->LockRect( &sLockedRect, NULL, D3DLOCK_READONLY );

pSourceFrame = sLockedRect.pBits;

pitch = sLockedRect.Pitch;

// COPY THE FRAME

CopyFrame( pSourceFrame, pSysFrame, pCacheBuf,width, height, pitch );

pDecoderRenderTarget->UnlockRect();

// DO SOMETHING WITH THE FRAME

ProcessFrame( pSysFrame );

}

Calling the Fast Frame Copy A fast video frame copy needs a pointer to the source frame buffer and its pitch (row to row byte distance), as well as the width, height and pixel format of the frame. In the sample code of Figure 4-1, all of this information is extracted for each frame. However, only the source frame buffer pointer usually changes from frame to frame during decode of a single video clip, so all but the particular frame pointer can be obtained and saved during initialization for that playback, reducing overhead during frame processing.

Some video codecs allow the frame width and height to change during playback, making it necessary to re-collect the frame and buffer size information, taking care to associate the new frame information only with frames actually affected - some frames associated with the previous frame description will likely still be in buffers at the time the new description is obtained.

Obtaining Frame Information The pointer to the buffer, and the pitch of that buffer, can be obtained by locking the Direct3D* surface associated with the frame for reading using the LockRect() function. Locking the surface as “read-only” (D3DLOCK_READONLY) informs the hardware video decode acceleration driver that no changes will be made to the frame buffer, but it needs to keep the buffer available and unchanged until the surface is unlocked using the UnlockRect() function.

Locking the surface as read-only should mean that the resulting D3DLOCKED_RECT will simply point to the actual USWC memory buffer. Locking without the read only flag would cause the driver to copy the frame buffer to a WB memory buffer, and copy its contents back to USWC memory when the surface is unlocked. As shown in the sample copy calling code, the width and height and frame format would generally be associated with the D3DSurface*.

Summary

Copies from USWC memory can be dramatically accelerated through application of the Intel® architecture streaming load and store instructions, using a well optimized copying algorithm. This should be useful for copying hardware decoded video frame buffers from graphics memory to system memory, and can with modest effort can be integrated into a DXVA* based application to enable software processing of decoded video frames.

References

“Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manuals”, (Includes the Optimization Reference Manual), Intel Corporation, http://www.intel.com/products/processor/manuals/ “Increasing Memory Throughput With Intel® Streaming SIMD Extensions 4 (Intel® SSE4) Streaming Load”, Ashish Jha and Darren Yee, November 17, 2008, /en-us/articles/increasing-memory-throughput-with-intel-streaming-simd-extensions-4-intel-sse4-streaming-load